When France fell to Nazi Germany in June 1940, a new collaborationist government called Vichy France took control. This authoritarian regime aimed to turn all citizens into loyal, unquestioning followers. Political opposition was outlawed, and even children were swept up in the growing worship of its leader, Marshal Pétain. Across North Africa, Muslim men and women were required to participate in elaborate public ceremonies declaring their loyalty to the new state.

By late 1940, colonial officials started enforcing antisemitic race laws. Jewish professionals were fired from their jobs, Jewish students were kicked out of schools, and Jewish-owned businesses and properties were seized and handed over to non-Jews. Making matters worse, as typhoid fever spread across the region, hundreds of Jewish doctors were forced to shut down their clinics. Algerian Jews, who had been French citizens since 1870, also had their citizenship stripped away

At the same time the economic situation deteriorated. Even though the authorities had put strict rationing in place, they couldn't provide people with enough food, clothing, and other basic necessities. Prices skyrocketed by as much as 600%.

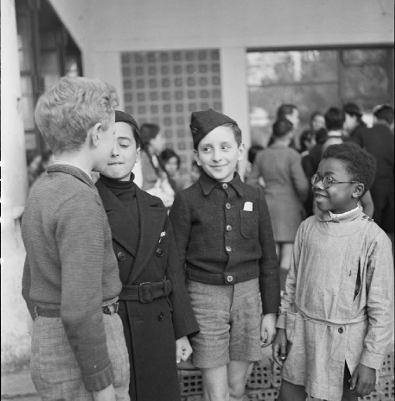

When Allied forces landed on November 8, 1942, North Africa began to open up politically. People who had opposed Vichy rule now demanded justice for what had happened. But this new freedom didn't extend to everyone. Muslims remained locked out of political power, and Algerian Jews had to wait until fall 1943 to get their French citizenship back. Even though the new "Fighting France" government was fighting against Nazi Germany, it kept the same racial divisions that had always supported colonial rule. Living conditions actually got worse, and ordinary people continued to struggle.

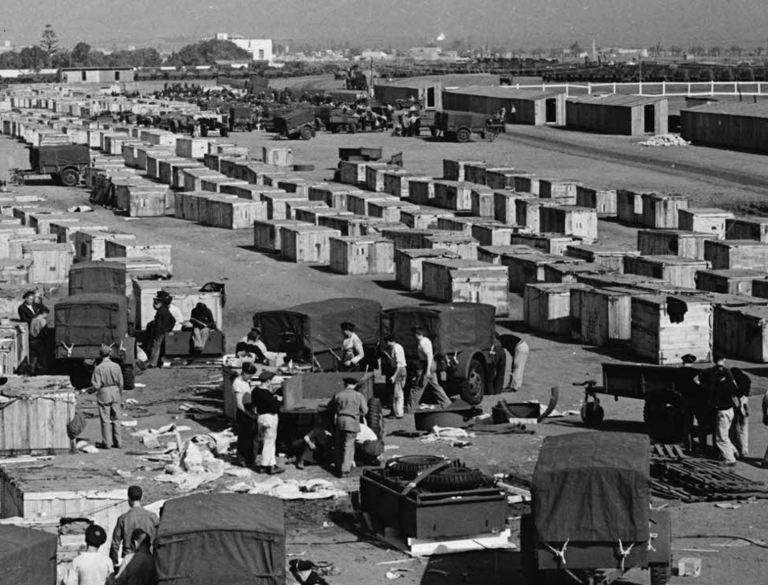

Winning the war in Europe depended on American supplies and the efforts of hundreds of thousands of North Africans—Muslims, Jews, and European settlers alike. This truly was a people's war, and North Africa's inhabitants contributed in countless ways. Service in the French army became an economic lifeline for many rural communities.